For reasons unclear to all, we’ve had quite the run (!) on norovirus cases in the United States this winter. Seems like everyone knows someone who’s been taken down by this nasty illness, and this crowd of miserable people includes one of my medical school classmates, a good friend who texted us about her experience.

For reasons unclear to all, we’ve had quite the run (!) on norovirus cases in the United States this winter. Seems like everyone knows someone who’s been taken down by this nasty illness, and this crowd of miserable people includes one of my medical school classmates, a good friend who texted us about her experience.

Thanks for sharing, Diane, speedy recovery!

So here are ten interesting facts worth knowing as you wisely head to the sink to wash your hands again before eating:

1. It is the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis in the world. This chart-topping characteristic of norovirus is probably even more impressive now that the rotavirus vaccine is available, dropping childhood cases from that virus dramatically.

In case you’re wondering, “acute gastroenteritis” just means diarrheal disease of sudden onset that lasts less than 2 weeks and may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever.

2. It was discovered after studying stored stool specimens collected during a community outbreak from 1968. That outbreak involved half (!) the students at a school in Norwalk, Ohio — hence the name, “Noro” gets its first syllable from “Norwalk”. I guess the citizens of that town didn’t want to be remembered for this dismal week.

Before the identification of virus, scientists strongly suspected a transmissible agent for this illness for obvious reasons. Not only was the attack rate so high in that school, but some of the family members of those students (who had not been in the school) came down with a similar illness.

Researchers then conducted some highly disturbing (from an ethical standpoint) human challenge experiments from specimens collected during this same outbreak, proving that it was, in fact, contagious. Can you imagine trying to get studies like this through a human subjects committee today? Awful.

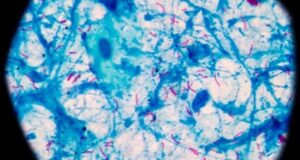

The actual publication of the pivotal paper documenting discovery of the virus wasn’t until 1972, when advances in electron microscopy allowed identification of the culprit critters from four years earlier, shown in this image:

3. Cases of norovirus peak in the winter months. In fact, the illness was once called “winter vomiting illness” due to this seasonal peak, with this generic term used prior to the discovery of the causative agent. Why winter? Humans gather indoors, huddling together against the cold, passing respiratory viruses between each other in the air, and viruses like norovirus in contaminated food, water, and surfaces. Fun times!

It was also called “non-bacterial gastroenteritis” to distinguish it from salmonella, shigella, and other causes of diarrhea that could be diagnosed by cultures. These “non” labels in medicine have always amused me — describing something by what it is NOT. You know, “non-A, non-B hepatitis” before we knew about hepatitis C, or “non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM),” a term still in broad use despite way more NTMs than TMs. Weird.

(I still miss NASH — non-alcoholic steatohepatitis — for fatty liver, an entity that seems to change its name every week.)

4. Infamous sites for norovirus outbreaks include cruise ships, daycare centers, recreational water parks, military barracks, nursing homes, and college dormitories. But especially cruise ships — go ahead, check out that link, I’ll be here when you get back.

… (waiting patiently) …

OK, now that you’ve seen the list of reported cruise ship outbreaks just in the past year, do you still want to take that winter cruise? Fact: any place or situation that people gather in close settings, and where contaminated food, water, and surfaces are hard to control, can trigger these outbreaks. How about particular foods? Oysters are often mentioned, which is no surprise at all, giving me an additional reason to avoid these slimy beasts*.

(*Easy for me to say since I don’t like them. Hardly a sacrifice. Feel very fortunate it’s not chocolate, or pizza.)

5. The incubation period is typically 24–48 hours after exposure. However, this doesn’t mean a person is “in the clear” after a couple of days if they don’t catch it in a household, on a cruise ship, or a dormitory that has active cases, for reasons that will be plainly evident in the next scary facts about the durability and ubiquity of norovirus in our world.

6. While norovirus shedding peaks during the acute illness, the virus can still be detected in stools for weeks in many people, small amounts can cause disease, and it’s devilishly hard to kill. The median time to loss of the virus is a month. Wow. A decent proportion of asymptomatic children shed the virus — nearly half in a study of kids in Mexico.

Plus, it’s an incredibly hardy virus — it resists freezing, heating to 60°C, and is not eradicated by alcohol-based hand sanitizers. I’ve heard this last phenomenon is because of the durable norovirus capsid, versus the much more fragile envelopes in other viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenza. I’m sure virologists have a much more sophisticated explanation.

One might wonder, reading these facts, why everyone doesn’t get norovirus all the time, or at least once every year. It comes down to those basic principles of infectious diseases, which are host factors (immunity, genetics, stomach acidity), inoculum size (how much virus found its way to you), and luck. Secondary attack rates might be high, but remember that sentinel outbreak in Norwalk — “only” half the students got it.

(For the record, my friend Diane’s husband is doing just fine. So far.)

7. After 1–2 days of utter misery from norovirus gastroenteritis, most people start to improve. During recovery, it’s not uncommon to have a week or so of feeling wiped out as one regains hydration and nutrition, but the general trend is favorable despite some ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms.

As with all infections, the disease is more severe for those at the extremes of age and people who are immunocompromised. For the latter group, illness can be prolonged, lasting weeks or even months, leading to profound weight loss.

8. There is no antiviral treatment for norovirus. Treatment is “supportive”, with the goal of maintaining hydration and getting at least some calories in during the acute phase. Remember, even people with cholera — the most notorious and life-threatening diarrheal disease of humankind — can absorb fluids when given liberally. So hydration is key.

What about during recovery? There’s lots of advice out there on the interweb, with variously recommended diets (e.g., bananas, rice, applesauce, toast — “BRAT” — clear broths, avoiding dairy products and spicy foods, etc.), but the reality is that we don’t have good evidence for any particular diet. I tell patients basically to eat what they want, in moderation, and to listen to what their bodies are telling them. The return of hunger is an excellent sign a person is on the mend.

9. The diagnostic test of choice for norovirus is stool PCR. Many laboratories now do molecular tests first — not cultures — to evaluate the causes of diarrhea. Since it’s so common, norovirus is included in all the multiplex panels that test for multiple pathogens.

The increased use of molecular testing no doubt explains at least in part the increased incidence of this infection. But on the flip side, the vast majority of cases are never diagnosed — so whatever figures we see on incidence are no doubt a massive underestimate.

10. Prevention strategies include frequent hand washing, cleaning contaminated surfaces, and isolation of symptomatic patients. As noted above, despite both pre- and post-symptomatic viral shedding, the highest risk time for transmission is during the symptomatic phase of the illness. Will we ever have a norovirus vaccine? Perhaps, though there are plenty of obstacles.

So that’s 10. Actually way more than 10, see how your subscription brings you added value?

And as an additional bonus, listen to my brilliant colleague Dr. Mike Klompas speak in our postgraduate course. Check out his #1 tip for infection control — for norovirus, it’s gold!