Durable and attractive, engineered stone countertops are a popular feature in modern American kitchens, but the workers who build them are risking their health. A growing number of these countertop workers are developing silicosis, a serious and long-term lung disease, according to a study being presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

This is a new and emerging epidemic, and we must increase awareness of this disease process so we can avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment for our patients.”

Sundus Lateef, M.D., study’s lead author, diagnostic radiology resident, University of California in Los Angeles

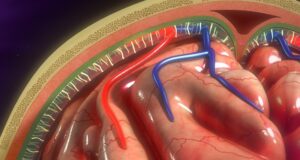

Silicosis is caused by the inhalation of crystalline silica dust produced in construction, coal mining and other industries. The prognosis is poor, with gradually worsening lung function leading to respiratory failure. The disease also makes patients more vulnerable to infection in the lungs, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, autoimmune disease and lung cancer.

In recent years, a resurgence of silicosis has been reported in engineered countertop workers. Engineered stone countertops are made from quartz aggregate held together with a resin binder. They contain substantially more crystalline silica than natural stone versions. Workers who cut, shape, grind and polish these countertops may be exposed to significant amounts of silica dust.

For the study, Dr. Lateef and colleagues studied the imaging features of silicosis at a large urban safety-net hospital outside of Los Angeles with few historic cases of the disease. The study group included 55 engineered stone countertop workers diagnosed with silicosis using available CT and pulmonary function tests.

In a preliminary analysis of 21 workers, 100% were male and Hispanic with median age of 43 years and a median exposure of 18 years. All patients were symptomatic. Patients commonly had atypical and advanced features of silicosis. Shortness of breath and cough were the most common symptoms.

Primary clinicians recognized silicosis at the initial encounter in only four of 21 cases (19%), while radiologists recognized it in seven of 21 cases (33%). Alternative diagnoses, such as infection, were initially suggested in most cases. Nearly half of the patients (48%) had atypical imaging features.

“Silicosis may present with atypical features that may catch radiologists off guard in practice regions where silicosis is not traditionally diagnosed, which can lead to delays in diagnosis,” Dr. Lateef said.

The results highlight a need for more awareness and better recognition of imaging features associated with silicosis.

“These new cases of silicosis demonstrate radiology findings different from the historical disease, and doctors may not be aware of the diagnosis when they see these images,” Dr. Lateef said.

Silicosis is preventable with workplace safety measures such as proper ventilation, wet cutting and sanding, and respiratory protection. However, research has shown that more than half of California workplaces exceed the maximum permissible exposure limit to silica dust during workplace inspections. Exacerbating the problem is the fact that many workers are Spanish-speaking Latino immigrants who are vulnerable to unsafe workplace conditions.

“There is a critical lack of recognition of exposure and screening for workers in the engineered stone manufacturing industry,” Dr. Lateef said. “There needs to be a push for earlier screening and advocacy for this vulnerable population, which in our case were Spanish-speaking immigrant workers.”

As part of an effort to improve screening and advocacy for workers, Dr. Lateef and colleagues are working on the ongoing California Artificial Stone and Silicosis (CASS) Project. The project aims to promote respiratory health among vulnerable workers in the state’s countertop fabrication industry.

Co-authors are Andrea Oh, M.D., Jonathan Hero Chung, M.D., Jane Fazio, M.D., Nader Kamangar, M.D., M.S., Sheiphali Gandhi, M.D., M.P.H., Robert J. Tallaksen, M.D., and Karoly Viragh, M.D.