Depending on which corners of the internet you’ve been hanging around in lately, how much protein you eat is either the single most important factor determining your health and athletic performance, or an overhyped and overconsumed indulgence that’s driving you to an early grave. The truth is obviously somewhere in the middle—but where, exactly?

Last month, the University of Toronto’s Tanenbaum Institute for Science in Sport hosted a conference on high-performance sports science. Along with deep dives into esoteric topics like NBA motion-capture data, artificial intelligence in pro sports, and international rules about intersex and transgender athletes, attendees got a practical primer on the current state of knowledge about protein for athletes from University of Toronto professor Daniel Moore, one of the world’s leading experts on the topic.

Moore’s talk addressed a series of commonly circulated protein myths, misconceptions, and truths. Some of the points were ones that I’ve written about recently—most notably, the question of whether very-high-protein diets damage your kidneys, and the idea that you can only digest a certain amount of protein at a time. Others addressed longstanding debates about the what, when, why, and how much of protein. Here are some of the highlights I took from the talk.

Protein Isn’t Just About Muscle

The fundamental goal of training is to trigger a cycle of recovery and adaptation in your body so that it gets stronger. That recovery process involves refueling, rehydrating, and repairing the cellular damage done by your workout so your body can build back better.

We usually think about protein in the context of repair—and for good reason. On any given day, you’re breaking down 1 to 2 percent of the muscle in your body and rebuilding it. Hard training increases that number. Overall (as muscle physiologist Luc van Loon notes), that means you’re completely rebuilding your body every two to three months. The protein you eat provides the amino acids that serve as the building blocks for repairing existing muscle and adding new muscle.

But protein can also play a role in refueling and rehydrating. Moore points to research showing that downing a recovery drink containing carbohydrate and protein rather than just carbohydrate after a hard workout helps your muscles restock their glycogen—the form in which your muscles store carbohydrate—more rapidly. Similarly, there’s research showing that protein can increase fluid retention when you’re dehydrated, which is one of the reasons that milk is sometimes tipped as a good recovery beverage. There’s even research suggesting that protein helps you acclimatize to heat training more effectively.

It’s worth noting that the enhanced post-workout glycogen storage with protein seems to only matter if you’re taking in less-than-optimal amounts of carbohydrate. More generally, as long as you’re not trying to survive exclusively on sports drinks, you’re likely to get whatever protein you need for rehydration and heat acclimatization and so on from whatever food you eat. But these studies offer a useful reminder that protein isn’t just a set of inert building blocks for muscle: it plays numerous roles in your metabolism that are crucial for both health and athletic performance.

Endurance Athletes Need Protein Too

The cliché of the gym bro with his tub of protein powder is firmly entrenched. Endurance athletes are less interested in—and sometimes actively averse to—packing on muscle. But their protein needs might still be elevated. The repeated pounding of running generates muscle damage that requires extra amino acids to repair. And previous studies have found that endurance athletes can get 5 to 10 percent of the energy they need by burning excess protein rather than incorporating it into their muscles.

Last year, Moore and his team published a study in which endurance athletes completed a series of runs ranging from 5K to 20K over several days, then consumed a batch of amino acids tagged with a special molecular label to track their progress through the body. The method enables scientists to determine how much protein is being incorporated into muscles, and how much excess protein is being burned as fuel. By repeating the running protocol while consuming different levels of protein intake, they can determine how much protein is needed to meet the body’s muscle repair needs before you start simply burning the excess for energy.

On average, they found that the runners needed about 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day to max out muscle-building and repair. The average value means that half the runners were meeting their needs and half weren’t; a safer threshold, where 95 percent of runners will max out their protein requirements, is 1.8 to 1.9 g/kg/day. In contrast, the RDA for protein is just 0.8 g/kg/day, and previous recommendations for endurance athletes were 1.2 to 1.4 g/kg/day.

The takeaway, then, is that yes, endurance athletes need more protein than the average person. But there’s one further wrinkle. Endurance athletes also need more calories overall than the average person. When you’re training hard, there’s a good chance you’ll eat so much that you get all the protein you need without any extra effort. One study of Dutch endurance athletes found that they were getting 1.5 g/kg/day, which is at least in the ballpark of Moore’s numbers. So you don’t need to go crazy on the protein.

Does More Protein Mean More Muscle?

It’s worth comparing those numbers to the latest data on what it takes to optimize strength and muscle growth. The best current evidence is summed up in a 2018 meta-analysis in the British Journal of Sports Medicine that pooled the results of 49 studies looking at protein supplementation and resistance training.

The key result is that consuming more protein led to bigger gains in muscle mass—up to a point. The breakpoint in their analysis was 1.6 g/kg/day, beyond which taking more protein didn’t produce bigger muscles. The data is messy, so I wouldn’t take that number as the absolute final word on the topic, but it’s notable that it’s roughly the same as the estimated need for endurance athletes. Taken as a whole, the evidence at this point doesn’t support the idea that mega-doses of protein—3 g/kg/day, say—are useful.

An interesting footnote: while the relationship between protein intake and muscle mass (up to 1.6 g/kg/day) was clear, the relationship between protein intake and strength was much weaker. There’s obviously a link between muscle mass and strength, but gains in strength also depend on neural adaptations and skill acquisition in the exercise that you’re testing. The positive spin on this is that it’s possible to get much stronger even if you’re not putting on a lot of new muscle.

Whey Isn’t the Only Way

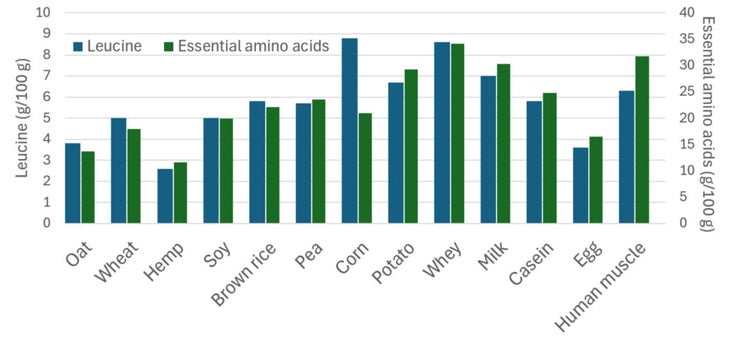

The “leucine trigger” hypothesis is the idea that the synthesis of new muscle depends in part on the levels of one specific amino acid, leucine. Milk, and in particular whey protein from milk, happen to be particularly high in leucine and other essential amino acids. Here, from a 2018 study in the journal Amino Acids, are the leucine levels and total essential amino acid levels of various protein sources:

You can see that whey is high in leucine and more generally in essential amino acids. But it’s not the only option: corn is surprisingly high in leucine, though its overall level of essential amino acids is lower, and there are lots of other reasonable options. A couple of studies published this year have put this idea to the test: one found that the synthesis of new muscle was the same after consuming corn or milk protein; another found that a blend of pea, brown rice, and canola protein matched the muscle-building performance of whey.

This doesn’t mean that all protein sources are created equal. But it does suggest that, with a little effort and attention, you can get all the muscle-building power you need from many different protein sources.

The Four Rules of Protein

It’s easy to get lost in the minutiae of leucine levels and recommended intakes and optimal timings. Moore finished his talk with four pieces of practical advice for athletes looking to get the most out of their training:

- Eat regularly spaced meals and snacks, three to five hours apart.

- Aim for ~0.3 g/kg/day of protein each time.

- Focus on real food when convenient.

- Make sure to meet your overall daily energy and macronutrient needs.

These seem like solid—and attainable—guidelines to me. If you weigh 150 pounds, 0.3 g/kg/day works out to about 20 grams of protein per meal. A tuna sandwich will get you there; two eggs (each of which likely contains 6 or 7 grams of protein) won’t quite do it unless you add some toast and milk.

As I noted at the top, recent findings suggest that (contrary to the prevailing orthodoxy) you can make up for a low-protein or missed meal by getting extra protein at the next one. I don’t think we know enough to be too dogmatic one way or the other, but the big picture seems clear: at the end of the day, if you want to optimize health and maximize athletic performance, you need to ensure that you’ve taken in enough protein to fuel your training and recovery.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.