Weill Cornell Medicine researchers have received a five-year $6.2 million grant from the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, to build a portable, high-resolution Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanner that can detect the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Unlike current models, this PET scanner will be upright, so a patient can sit in a chair that travels with the unit, significantly improving portability and accessibility. “We can move it to medical centers that might not have advanced brain imaging, enabling us to provide the highest-level care to more diverse populations,” said Dr. Amir H. Goldan, who was recruited to Weill Cornell Medicine as associate professor of electrical engineering in radiology.

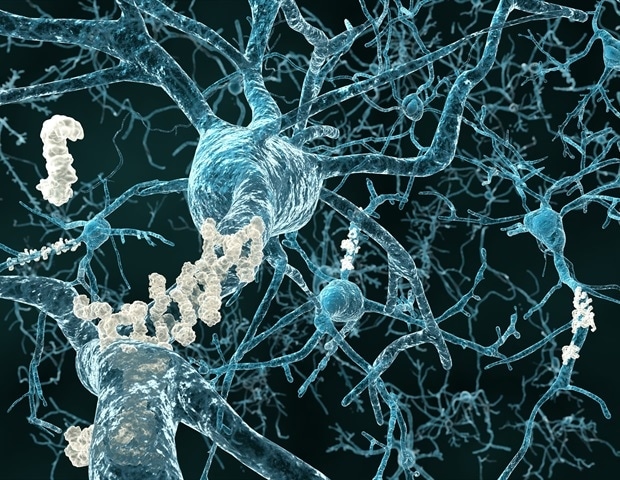

When getting a PET scan, a radioactive tracer is injected into the bloodstream, which is taken up by the targeted tissue and emits a signal that the PET scanner detects. This is then translated into an image. However, current scanners have poor spatial resolution that limits image quality and can’t provide reliable quantitative information on biomarkers, such as amyloid plaques and tau tangles, which are protein clumps found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

Detecting the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease

The grant follows a proof-of-concept study in which Dr. Goldan and his colleagues developed a PET scanner with the world’s highest resolution. This scanner, called Prism-PET, can detect “hot spots,” or areas of increased concentrations of radioactive tracer, less than 1 mm in diameter when tested within brain phantoms, which are objects that simulate human tissue. Commercially available PET scanners produce significantly less detailed images.

For this new grant, Dr. Goldan will collaborate with Dr. Gloria Chiang, associate professor of clinical radiology and director of the Brain Health Imaging Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine, to use Prism-PET to detect tau tangles in the transentorhinal cortex, a network hub for memory, navigation and the perception of time.

This is the earliest site where tell-tale tangles form, indicating Alzheimer’s disease even before symptoms such as mild cognitive impairment appear.

The transentorhinal cortex is only a few millimeters in size and can be incredibly difficult to accurately image with conventional PET scanners, even with highly specific tau PET tracers.”

Dr. Gloria Chiang, associate professor of clinical radiology and director of the Brain Health Imaging Institute, Weill Cornell Medicine

The scientists also aim to refine motion compensation to reduce blurring on PET images due to patient movement.

Dr. Goldan is also collaborating with Dr. Jinyi Qi, professor of biomedical engineering at the University of California, Davis and co-principal investigator on the grant, and an advanced medical imaging systems company.

Early detection could mean earlier treatments

With the 2023 FDA approval of lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody that targets amyloid plaque and the only treatment shown to slow the progress of Alzheimer’s, the demand for PET imaging has skyrocketed. “To get the therapy, you first need to undergo brain imaging—a portable PET scanner for the brain will help meet this demand,” Dr. Goldan said.

The scanner has such a small imprint that even community hospitals and other healthcare facilities don’t need a dedicated space for brain PET imaging. Another possibility to meet demand is using the scanner in a truck as a mobile PET imaging unit that can travel where needed such as underserved areas.

“Our overall goal is two-fold—having the highest performance brain PET scanner available, while also addressing its accessibility and portability to serve the community,” Dr. Goldan said. “The earlier you can diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, the better the chances of therapy being effective.”